Is design no longer fun?

Deep Dive

02.01.2026 - by ALEXANDER KRANZ-MARS

It's been a long time since I asked myself whether I actually enjoy design. It's a question you rarely ask yourself in everyday life. And yet positive emotions and the desire to create are important in order to achieve an impact with design.

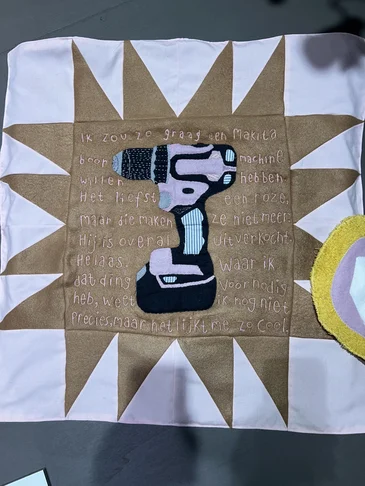

As a teacher at the School of Design at GBS St.Gallen, I accompanied the 2nd and 3rd year of the Fachklasse Grafik on their cultural trip. I spent a week in a country that not only invented the fun of design, but still makes it visible today. In a city where creativity and the joy of experimentation extend into all areas. Unmissable, especially in architecture. Not only surprising and provocative, but also playful and experimental.

A week in Rotterdam reminded me of the joy of design and that design and fun can go together and that design should also provoke. The expected is boring average. Predictability is not a unique selling point.

The joy of design is clearly evident in the crazy shapes of the buildings, the unusual façades and the playful lighting concepts. From the outside to the inside, the lively diversity is conveyed through signage systems, labelling and brand elements. Museums and temples of culture in particular stand out not only for their daring arrangements, but also for their modern and unique branding. Design here is not only fun for the designers, but also for those who commission it.

Starting with the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, which offers an additional unusual museum experience in combination with the depot, to the newly opened Fenix with its impressive tornado staircase and the Huis Sonneveld, which impressed me as a modern work of art built in 1933. The architectural style, interior and furnishings form a coherent concept, harmonised down to the smallest detail, which was tailored to the life of the Sonneveld industrialist family with sophisticated technical features.

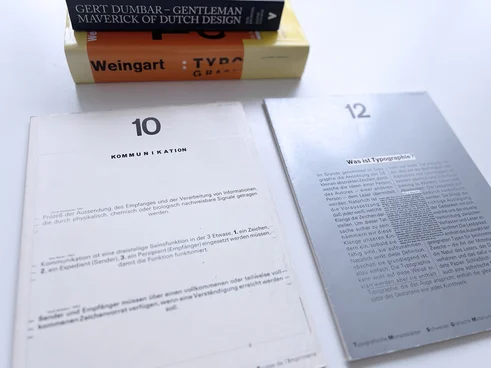

My last cultural trip with a «class» was some time ago. When I was studying design in Germany in the 1990s, we travelled to Basel to see Wolfgang Weingart. I immediately noticed that Switzerland was different from Germany in terms of design. You could see well-designed adverts and posters everywhere in the city. In Weingart's classroom, on the other hand, his black-and-white systemic, two-dimensional experiments with letters, sentences and paragraphs had a similarly repetitive and exhausting effect on me as the designs that were the benchmark at my design college in Schwäbisch Gmünd. Both were intended to make everyone notice: Design is really hard work.

Although Germany's design history also boasts world-famous designers, outside of my designer bubble in the nineties I felt I had to explain to all non-designers that graphic design is a profession and is considered to be quite systemically relevant in certain areas.

The trade schools in Basel and Zurich, on the other hand, recognised the need for professional design early on and officially introduced the profession of graphic designer in Switzerland in 1915 (!). The difference in society's perception and appreciation of design and designers was clearly noticeable to me when I moved to Switzerland.

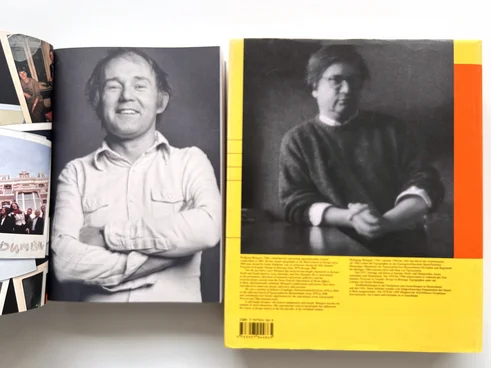

During my studies, I noticed another country that differed from Germany in terms of design: the Netherlands. As in Switzerland, design has a recognisable place in the cityscape. Gert Dumbar's design for the Dutch police force: unimaginable in Germany. In the Netherlands, it has been in use almost unchanged since 1993 and is also popular. And the Swiss export hit in terms of design: the Helvetica font. In use worldwide since 1957, cool but modern and timeless. Nevertheless, when it comes to graphic design, Switzerland and the Netherlands are worlds apart.

I realised this when I began to compare the two cultural journeys. Weingart influenced designers worldwide in the early 1980s with his new design and inspired them to experiment and take a freer, more playful approach to typography. Weingart was a student of the Zurich School, which was known for its strict, clear and rational typography. Grid, order, Helvetica. But Weingart turned this system on its head. He began to deconstruct letters, to superimpose typefaces, to break the grid. His work was a rebellion against the sterile perfection of the Swiss style under Emil Ruder.

While Weingart's design seemed more like a liberation than a good humour, fun and the joy of creative experimentation and provocation spread like wildfire to all areas of design in the Netherlands, starting with Gert Dumbar and others.

Weingart and Dumbar could not have been further apart in terms of design. Dumbar combined humour, theatricality and visual surprise with a clear intention to communicate. While Weingart destroyed the grid, Dumbar turned it into a colourful stage set. His style was playful, narrative and emotional. In other words, typically Dutch in its openness and irony. Where Weingart questioned typographic systems, Dumbar questioned social conventions.

During our stay in Rotterdam, we also had the opportunity to visit Studio Dumbar/DEPT under the direction of Liza Enebeis. And there it was again: the joy of design. Humour, colour, typography, emotions: everything in motion.

Although I didn't have the feeling that I had to look for the fun in design again, I was surprised to suddenly be presented with it in such a concentrated form. Had I lost sight of it recently? Fun is the motor that generates ideas and gives design the necessary vitality.

Rotterdam reminded me that design requires attitude. Courage, curiosity and the will to fill the world with design that is fun, humorous and meaningful. Design that stands out, takes centre stage and gives people something to talk about.

That's where the fun begins. And that's exactly where I want to get back to.